What is glass?

a teaching aid

Glass is one of the most widely used materials in the world: it is found in everyday objects like bottles and light bulbs, as well as the windows of our houses and buildings. But what exactly is glass? It starts out as a lowly material: literally the sand under our feet. If heated high enough, to about 1723 degrees centigrade (°C), sand can melt and turn into a liquid. However, this does not happen easily: you would need lightning or a volcano to do so. In order to lower the melting temperature of sand to what can be achieved in a fire or furnace, and make it more workable as a liquid, it is mixed with materials called “fluxes.” The most common fluxes come from ashes of plants that contain sodium carbonate (soda ash) or ashes of trees that contain potassium carbonate (potash), and these are mixed with substances like chalk (calcium carbonate). When the liquid sand mixture is cooled very rapidly, the sand transforms into a special material we call glass, which is now hard, bulky, transparent and brittle.

From a chemistry point of view, the physical properties of glass arise from the rapid cooling stage, which causes the atoms that make up the quartz pebbles in sand—silicon (Si) and oxygen (O)--to become solid in the same kind of disorganized arrangement as they were found in the liquid form. This type of structure is called “amorphous.” Chemically, glass is a disordered network of silicon dioxide molecules, bonded together in what we call the silicate matrix. The atoms from the fluxes, such as sodium (Na) and potassium (K), arrange themselves near O atoms. This “frozen” liquid has a lot of stresses usually, which makes it brittle and easy to shatter or crack. In order to make glass less fragile, it is reheated at a lower temperature. In this way, some re-organization of the network happens, and a lot of the stresses relax.

How is glass made?

Glass can occur naturally or be man-made. Vitrified sand can occur when lightning strikes it, and natural glass called “obsidian” is formed from the heat of volcanoes and the rapid cooling of lava flows. Early humans found obsidian and often fashioned it into arrow heads and blades, which were hard and very sharp, and so highly prized and traded often. This natural glass is usually black in color because of other rocks that were mixed into the lava. Man-made glass might have been discovered by accident in the ashes of fires used for making other materials, like metal objects or clay pots. Once discovered, human ingenuity developed infinite ways to make and manipulate glass by pouring, pulling and molding the liquid glass, starting from ancient times to the present day.

Antiquity

Man-made glass stretches back to ancient Egypt and possibly dates to the 3rd millennium BCE in Mesopotamia. The geology of the Mediterranean and Middle East is naturally rich in sodium, so the ashes of plants from these areas have a lot of sodium carbonate, which is an excellent flux. This “soda ash” is an alkaline substance that lowers the melting temperature of glass raw materials (see above). When mixed with chalk or limestone, this type of glass is called “soda lime glass.” Early glasses were made into utilitarian objects by processes such as core forming.

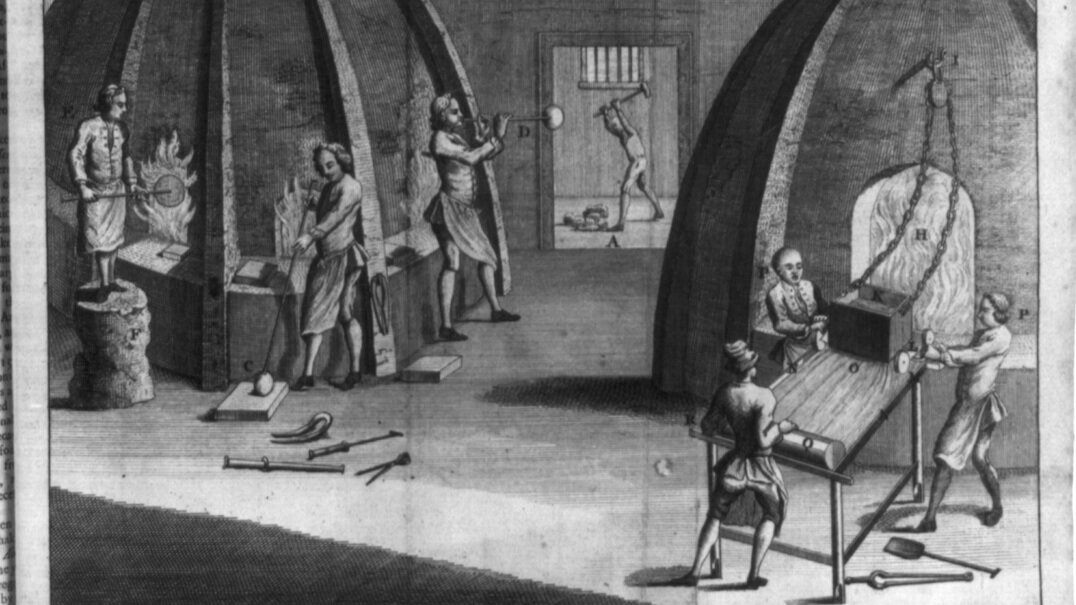

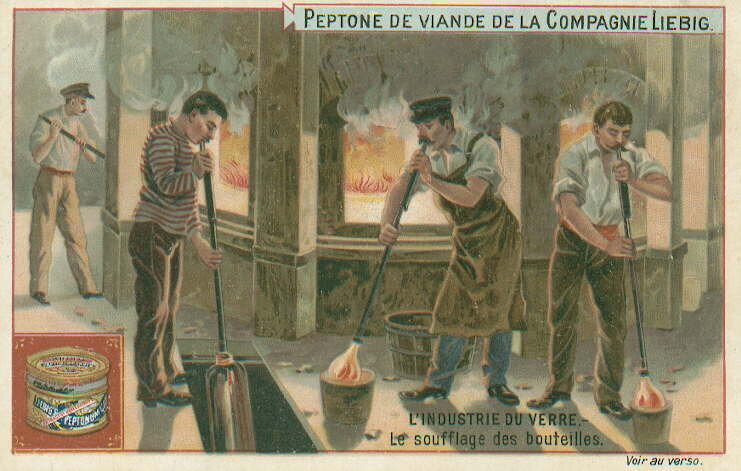

One of the first major innovations in glass-making happened in Roman times, when a glassmaker blew through a rod into molten glass, creating a bubble. This technique, called glassblowing, opened the door to the art of glass vessel-making and changed glassmaking forever. Roman blown vessel glass became a major industry and includes many examples of beautiful and whimsical objects.

Medieval and renaissance eras

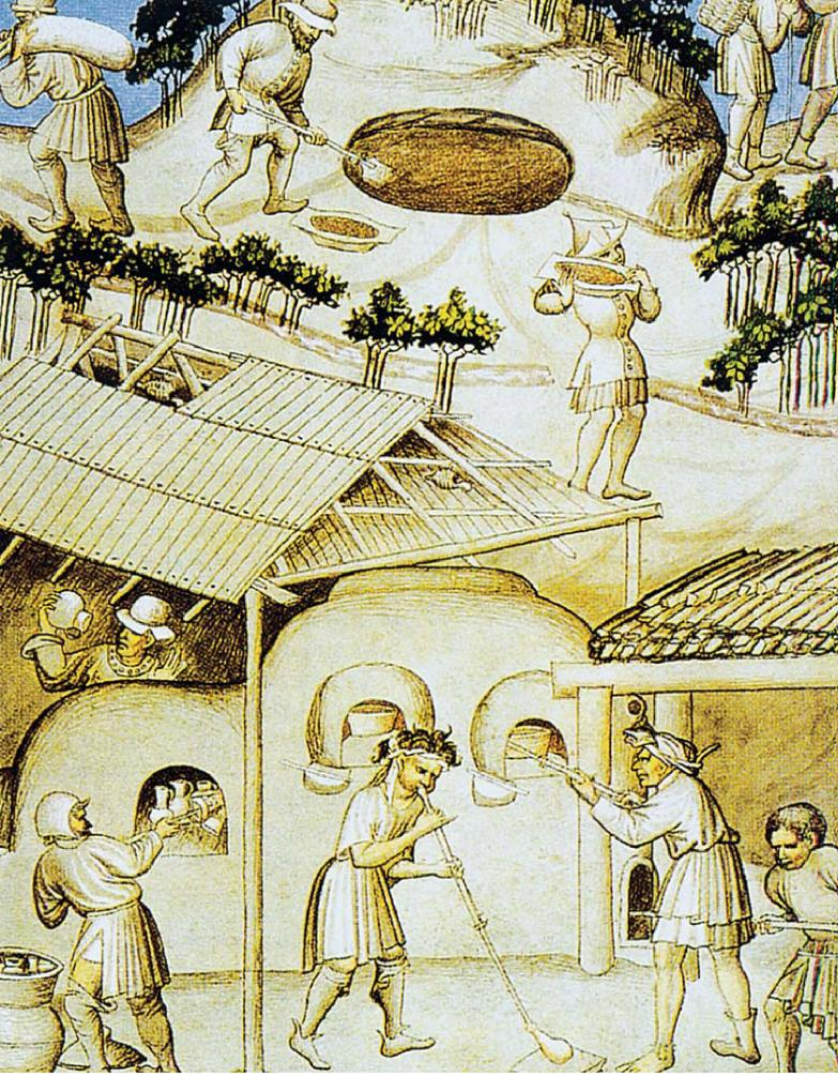

After the fall of the Roman Empire, glassmaking techniques were largely forgotten in Europe until about 1000 A.D. In central Europe, the vast forests supplied a large amount of ash from trees, and this type of ash is rich in potassium carbonate, another type of flux that allows glass to be made from sand at greatly reduced melting temperatures. This new type of glass is called potash glass, and also commonly called “forest glass,” not only because it is often green, but because the glass foundries were mostly located in the Bohemian forests.

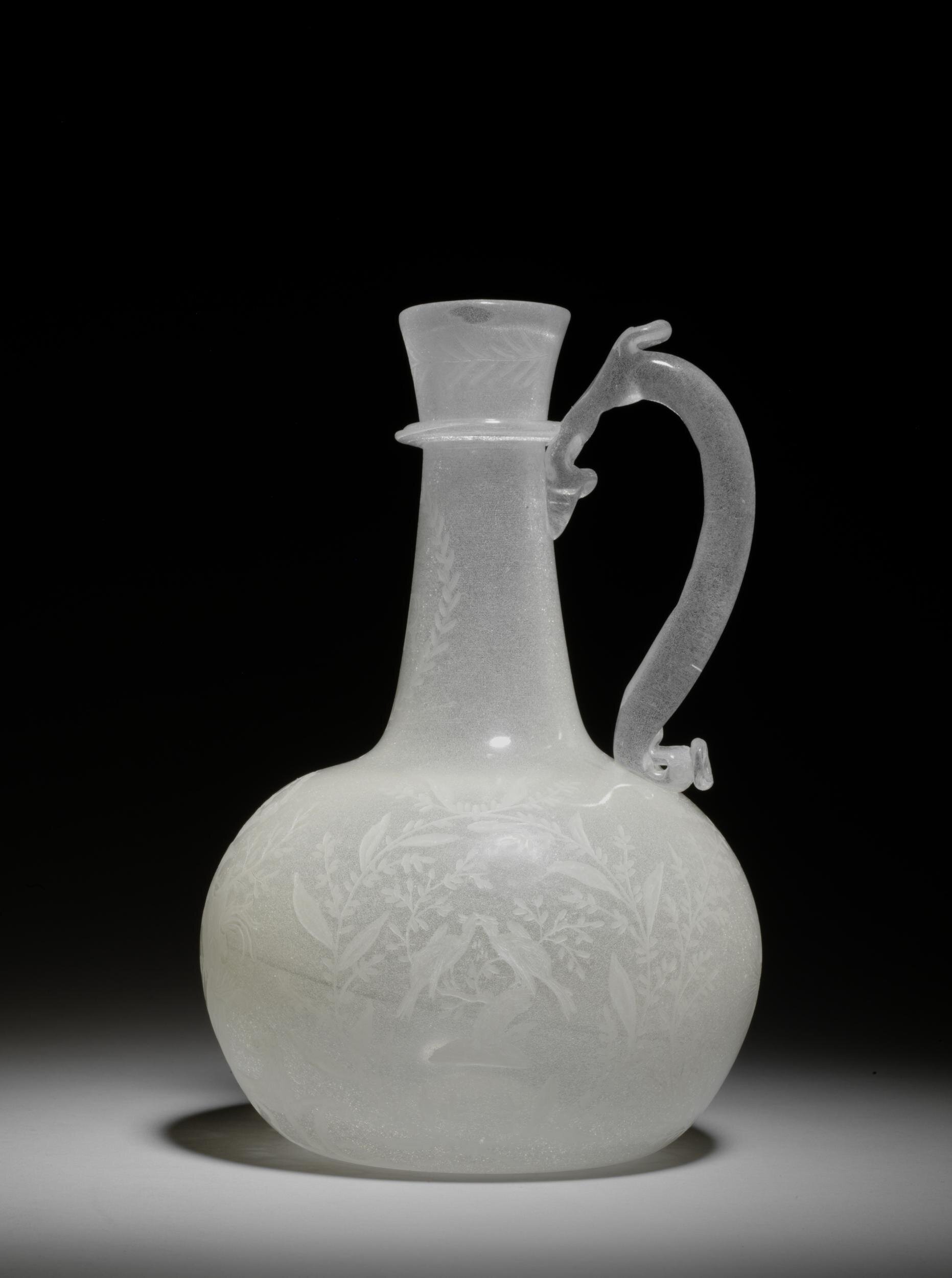

Glass produced before the Renaissance was normally colored green or brown, due to impurities in the sand, like Fe-containing rocks. Some minerals were purposely added to glass to turn it blue or red, for example. Colored glass was also important in medieval times to make the beautiful windows of churches. While glass could also imitate some types of gemstones, it remained difficult to imitate rock crystal, a rare and colorless form of quartz often used to decorate religious objects and carved into vessels. A major advance during the Renaissance was the invention of “cristallo” in Italy. Here Venetian glassmakers invented clear glass that imitated rock crystal using secret formulas that we now know contained manganese oxide in addition to very pure quartz pebbles and soda ash. Cristallo quickly became popular and was sought after by royalty.

In the 17th century, a man named George Ravenscroft worked in Venice for a time, then was commissioned in his native England to make clear glass that rivaled cristallo. Ravencroft’s experiments with a new type of clear glass, made using lead ores and much less flux, are usually held to be responsible for the invention of “lead crystal glass.” This new glass retained the name of “crystal” even though it is not crystalline like rock crystal, but amorphous like other glasses. Leaded crystal glass has some different physical properties than ordinary soda or potash glass, making it clearer and more sparkly, as well as easier to cut with patterns. Ravenscroft’s glass factory was the most successful in London, and this technology spread throughout Europe.

modern era

The 18th century Age of Enlightenment in many ways marks the beginning of the modern era in terms of the use of scientific principles rather than trial and error to advance technology, including in the glassmaking industry. Glass recipes became understood from a chemical point of view and became more refined, but glass remained expensive since it demanded great skill to manufacture. This was especially true for flat glass, which was highly in demand for both windows and mirrors, and were associated with wealth. In the 19th century, flat glass became a mass-produced commodity due to new automated polishing processes and better furnaces. This led to large decreases in the price of glass and its use for more everyday materials, including flat glass, which became very useful in the new field of photography.

In the 20th century, industrial glassmaking became completely automated, and many new types of glass and glassmaking techniques were introduced. “Crystal” glass has been replaced with non-leaded types, and Pyrex glass can withstand high cooking temperatures, for example. Glassmaking technology continues to expand in the present day, and glass remains one of the most important materials in the fields of engineering, design and art.

What are types of glasses?

The slideshow below shows different types of glass, dating from several millennia ago to the modern day. For more information about each type of glass, hover over the picture. To see the official object websites, click the image.

is glass stable?

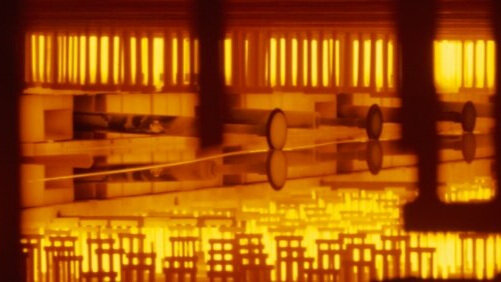

Surface deterioration and cracking around a tone hole on Laurent Flute DCM 1680, upper body joint.

Glass is not only fragile, but some types of glass degrade over time, even though most people think that glass is very stable. This has actually been known for a long time, since windows made from alkali silicate glass exposed to the weather often became covered with tiny pits and surface accretions over time. This looks like “fogginess” or opaqueness to our naked eyes. This can also happen to old drinking glasses that go through the dishwasher over and over, and to wine decanters that hold liquid for a long time.

To learn more about glass deterioration, click here.